I’ve always considered myself relatively invulnerable to phishing attacks, in which an attacker creates duplicate login pages that look like a system a victim would normally use, in order to dupe them into giving away their username and password. In contrast, less experienced web users are extraordinarily vulnerable to this kind of attack, since without a good understanding of how the web works, it’s almost impossible to tell real from fake.

About 10 days ago, the hacker or hackers calling themselves the Syrian Electronic Army (SEA) carried out a very targeted cyberattack against the FT. We’re not the first to be targeted and in fact as I write this we’re not even the most recent. But the experience taught me an important lesson. Targeted attacks against a single large corporation are not like the random, almost embarrassingly fake emails you get telling you to reset your PayPal account. They’re painfully, soberingly realistic. Those that were sent to the FT compromised scores of our corporate Google accounts. And one of those was mine.

How it happened

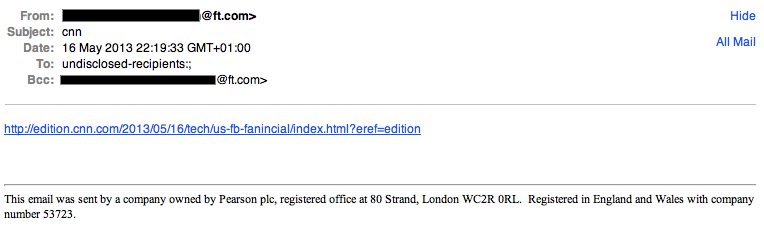

On May 14th, some emails containing a phishing link entered the FT from external email accounts. Some of these were from the personal accounts of FT staff, suggesting that they had already been targeted personally, even though the email account targeted was not technically associated with the FT. The emails contained a link, which appeared to be an article on CNN.com, but was actually a link to an already hacked WordPress site (rather a high profile one but we thought it rude to name them, and they’ve since fixed it). The site was hosting a file called ft.php. Because the email was HTML formatted, it could link to one URL while displaying another, so the link didn’t look like the URL it actually linked to:

The hacked WordPress site redirected the user to a page hosted on googlecom.webege.com, which looked identical to our corporate email login screen (the FT uses Google Apps for internal email).

If you submitted the form on the googlecom.webege.com page, the data was sent to a PHP script on the same host, and it then logged you into your real Google account and redirected you to GMail so you were none the wiser. We managed to cause some errors in the script, which suggested it was invoking a shell command using your google account data as command line arguments. We also reported the site to the web host, and later in the day, they took the site down.

By targeting those FT staff that advertise their email address publicly, the hackers eventually managed to secure access to an FT.com corporate email account. With this, they also had access to our global address list and with it the email addresses of every member of FT staff. They began sending the same email to a much larger number of FT.com users, this time from legitimate FT.com email accounts.

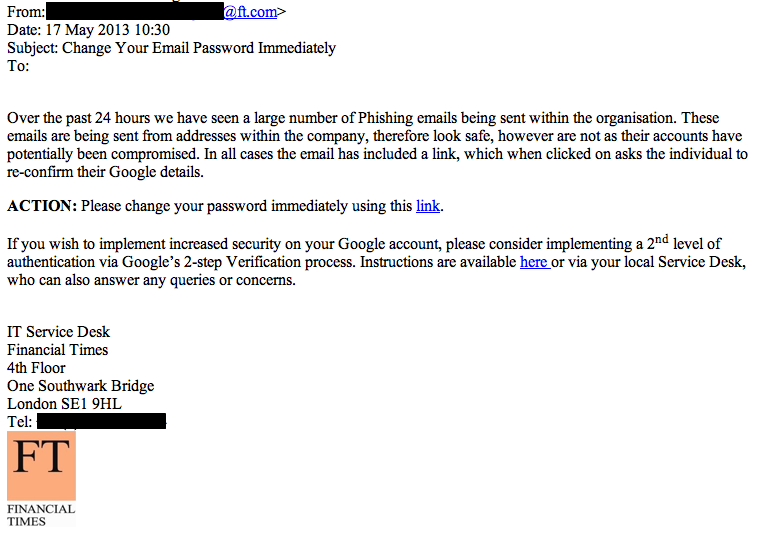

Our IT support team had received reports of the phishing, and issued an alert to all staff to ignore phishing emails and at the same time suspended the known compromised accounts. Unfortunately, this also gave the hacker better material – the alerts were in the inboxes of the hacked accounts, so the hackers adjusted the emails they were sending to use our IT service desk alert message, using the alert and people’s desire to be secure in the face of the attack to hook more victims:

At this point, we have an email using real FT terminology, coming from a genuine FT.com email address, asking users to log in and change their password, with a link to a login page for the exact email system that we use at the FT.

Eventually, the circulation of phishing links stopped, when Google blacklisted the URL. Future emails containing that link would now be bounced. But with the accounts they had already compromised, the hackers had managed to perform a password reset on a valid account for our blog platform, and also gain access to a number of our Twitter accounts. This was when we saw SEA content being published on FT channels – some of it with my name on.

Developers might well think they’d be wise to all this – and I thought I was. I got the email, and clicked the link, but then I recognised the phishing page for what it was and reported it without filling in the form. It’s been suggested to me that I might have left the tab open and inadvertently logged in later when switching tabs without looking at the URL, and I guess that must be what happened in my case.

How we responded

Our operations and development teams use a product called Splunk to collect and analyse logs in near real time. Google also provide us with access to a team who can access logs on their side. We began to build a picture of the attackers traffic patterns and identifying traits. We could start to track them with greater accuracy as they continued to try and access a variety of systems.

Meanwhile, we took action to lock down systems and get back control:

- We invoked IP restrictions, limiting access to many systems to those within an FT network

- The compromised Google accounts were all deactivated by Google

- Twitter locked all our Twitter accounts and changed the credentials

- We activated more aggressive measures to alert us to suspicious login attempts

Security lessons

The only two systems (other than the Google mail accounts) which were successfully compromised were Twitter (many of our accounts), and WordPress (two blogs out of around 60). Twitter and WordPress are probably the two most ubiquitous publicly accessible tools in use at the FT, so it doesn’t seem surprising that they were targeted. This problem will likely get worse over time as more organisations adopt the same online tools – if a vulnerability is found against one, it can be used against all – increasing the motivation for the hackers to find holes.

On the other hand, adoption of more ubiquitous tools is a good thing. Switching to Google accounts (a move which the FT completed last year) gives us access to a well designed two-factor authentication system and automated security checks that offer a much more robust defense. In a sense, although there may be more people banging on the door, the door is more solid. Unfortunately, on Friday, we discovered that we had left it ajar.

Having set tighter security standards, we’re also now re-auditing all points of authentication at which an untrusted user can be granted privileged access to an FT technology resource, reducing and removing privileges more aggressively where they are not absolutely necessary, educating and assisting users by setting clearer expectations of security standards, and improving our speed of detection and response when attacks occur. It seems complacent to think that we can close all possible vulnerabilities, and a swift and decisive response is a good second best to prevention.

Large organisations, especially media companies, will always be vulnerable to cyber attack – the attack surface is huge, and the attacker needs only a tiny chink in the armour. We reluctantly join an illustrious list of organisations that have suffered similar attacks in recent weeks – Associated Press, the Onion, Sky News, the BBC, the Guardian, and just a few days after us, the Telegraph.

Is this the end?

Not quite. We’re actually quite familiar with the hacker or hackers that call themselves the SEA, because we’ve written about their activities against media organisations several times. Our colleagues in Abu Dhabi actually made contact with the group through what appears to be the organisation’s official Twitter account, and interviewed them over email, which we also published.

In the wake of the FT attack, we contacted them again, and got this reply from their purported spokesperson (unedited):

Yes, we did hack the FT today to publish some information that all of the major news organizations have been ignoring. The bloody nature of the Syrian so-called “rebels” has been deliberately overlooked in favour of statistics distributed by various bodies and a single man in Coventry. All of the violence has been pinned on the Syrian Arab Army that is simply defending its soil.

The FT definitely is the less bias of the western media establishment so our attack was very light. We thought it was important for your financially concious viewers to observe the results of what their government was funding. We are disgusted to the core at William Hague and David Cameron’s recent allocation of 40 million pounds to fuel death and destruction in our country in order to obtain political concessions. This is terrorism by definition and we have evidence from a sky news hack that the FCO is directly involved in not only finance but procurement. No one we have contacted in the media was willing to run the story so we had no choice but to take matters into our own hands.

We have no further plans to hack the FT and we hope there are no hard feelings. We are only trying to save our civilization. Our voice is small we hope you can lend us yours.

This is a technical post about security, so I won’t comment on the above apart from to say that the activity we see from the SEA comes from Russia as well as Syria.

Hack culture

Rather ironically, we were hacked on a Friday, and the following Monday and Tuesday was the annual FT Technology Hack Day event. Hacking comes in many guises, and while some are destructive, others are creative. Here’s what hacking means to us:

Developers proudly wear T-shirts that say ‘Hacker’. Journalists are actually fondly referred to as ‘hacks’. We like hacking a lot. We just need to be better at keeping the hackers we don’t like from interfering with the hackers (and indeed, hacks) that we do.

Hack on.